The ability to watch (and sponsor) one’s favourite teams and athletes Veo has long been one of the most popular and successful media plays in the world, enticing broadcasters, sponsors, and consumers to shell out enormous sums.

Naturally, producing that material is quite expensive, further constricting the production and dissemination process. However, a startup today announced a round of funding to expand its business and target the long tail of sporting teams and fixtures. The startup’s autonomous, AI-based camera allows any team to record, edit, and distribute their games.

Veo Technologies, a Copenhagen-based startup, has raised €20 million (roughly $24.5 million) in a Series B round of funding. The company has developed a video camera and cloud-based subscription service to record and then automatically pick out highlights of games, which it then hosts on a platform for its customers to access and share that video content.

Chr. Augustinus Fabrikker of Denmark is leading the funding effort, and Courtside VC of the United States, Ventech of France, and SEED Capital of Denmark are also contributing. Henrik Teisbaek, the CEO and co-founder of Veo, claimed in an interview that the business does not reveal its valuation, although a person familiar with fundraising tells me that it is significantly more than $100 million.

According to Teisbaek, the money will be used to continue growing the company’s business on two levels. Veo will first focus on growing its U.S. business, opening a Miami office.

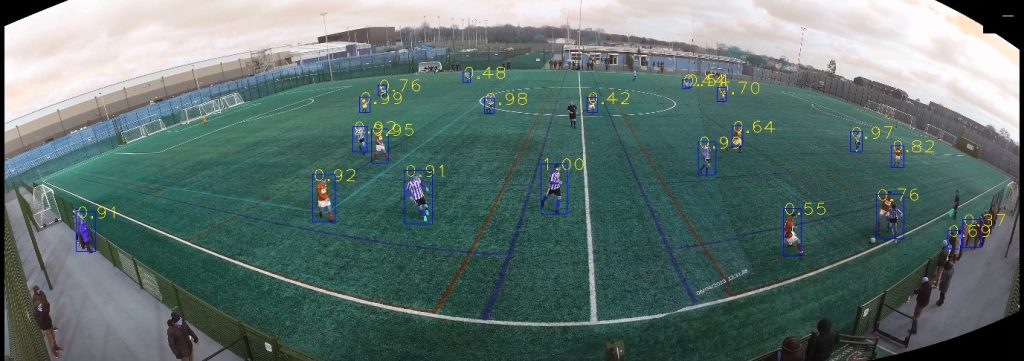

With customers purchasing the cameras, which retail for $800, and the corresponding (mandatory) subscriptions, which cost $1,200 annually, both to record games for spectators and to use the footage for all kinds of practical purposes, the company began by optimising its computer vision software to record and track the matches for the most popular team sport in the world, football (soccer to American readers). The cameras’ ability to be set up and left to operate independently is crucial. Once in position, they can film the majority of a soccer field (or other playing area) using wide-angles, zoom in, and then edit down based on that.

Now, Veo is developing the computer vision algorithms to extend that claim into a variety of other team-based sports, such as rugby, basketball, and hockey, and it is stepping up the types of analytics it can offer regarding the clips it produces as well as the overall match itself.

Veo has had significant growth despite the slowdown in a lot of sporting activity this year as a result of COVID — for instance, we’re once again in a lockdown when team sports below professional levels, with the exception of teams for disabled persons, have been banned.

The startup presently works with 5,000 groups worldwide, ranging from professional sports teams to amateur clubs for kids. Since it began operations in 2018, it has recorded and monitored 200,000 games, with a sizable percentage of that number occurring in the past year and in the United States.

As a point of comparison, Veo had 1,000 clubs and 25,000 games when we covered its $6 million funding round in 2019, indicating a 400% increase in users during that time.

The COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly changed the playing field for sports over the past year, both physically and figuratively. When it comes to preventing the transmission of the coronavirus, spectators, athletes, and support personnel must exercise the same caution as everyone else.

The NBA went to great lengths to create an expansive isolation bubble in Orlando, Florida, to play out the season, with no actual fans in physical seats watching games, but all games and fans virtually streamed into the events as they happened. This has not only changed how many games are played, but also for attendance.

Needless to say, the NBA effort came at a significant financial expense that any lower league would never be able to bear. As a result, this situation has given rise to an intriguing use case for Veo.

Before the pandemic, the Danish startup was quietly growing its clientele by targeting the long tail of sporting organisations that, even in the best of circumstances, would struggle to find the money to purchase cameras and/or hire videographers to record games, which are not only necessary for spectator enjoyment but also helpful for team building.

There is a misconception that football is already recorded and televised, but Teisbaek pointed out that only the Premier League does it in the U.K. “Nothing is being recorded if you move down one or two steps from there.” Prior to Veo, he continued, “you needed a man standing on a scaffold, along with time and money to edit that, in order to film a football game.” just the highlights Simply said, it’s too laborious. However, the best resource for skill development is video. Children learn best visually. Sending movies to universities is also a fantastic strategy to get recruited.

The pandemic then caused those use cases to grow, he explained. Video becomes a tool to track those matches because parents are not allowed to watch their children outside due to coronavirus regulations.

“We’re not an Amazon. We’re a Shopify.”

There will not be many spectators for each match, but there are millions of matches, according to Teisbaek, who described Veo’s economic strategy as largely based on “the long tail idea,” which works out in the case of sports. However, if you take into account how many high school sports will draw locals outside of those already associated with a school — you have alumni boosters and followers, as well as local businesses and neighbourhoods — even that long tail audience can be worth it.

Veo’s long-tail concentration has naturally led to its target users being in the wide range of amateur or semi-pro clubs and the people associated with them, but intriguingly it has also spilled into major names, too.

Professional soccer teams in the Premier League, La Liga, Serie A, and Ligue 1 all use Veo cameras, as do a number of MLS teams like Inter Miami, Austin FC, Atlanta United, and FC Cincinnati. Teisbaek pointed out that even while it might never be used for primary coverage, it is there to enhance training and can also be used at the academies associated with such organisations.

Longer term, according to him, the goal is not to exploit the wealth of content that the company has gathered to create its own media empire, but rather to enable its users to create content that they can then use anyway they see fit. Teisbaek emphasised that it is a “Shopify, not an Amazon.”

“We are not creating the next ESPN,” he said, “but we are using our technology to help the clubs unlock these linkages that are currently in place.” “We want to assist them in recording and streaming their games and performances for the current audience.”

He could see the opportunity that way, but some investors are already considering the wider picture.

Vasu Kulkarni, a partner at Courtside VC, said he’d been hoping to back a startup like Veo, establishing a smart, tech-enabled solution to capture and analyse sports in a more economical way. The firm’s portfolio includes The Athletic, Beam (bought by Microsoft), and many other sports-related businesses.

He claimed, “I spent nearly four years trying to identify a company trying to achieve that.

I’ve always thought that sports material should be discovered at the long tail, he declared. Unrelatedly, he founded a business called Krossover in his dorm room to assist in tracking and documenting sports training. Hudl, a rival, finally purchased Krossover to Veo.

The NBA Finals will never be recorded on Veo because there are simply too many factors at play, but when you start to consider all the areas where there isn’t enough mass media value to hire people, produce content, and livestream, you reach the point where computer vision and AI will be filming to eliminate the expense.

He claimed that the camera’s economics are crucial here: it must cost less than $1,000 (which it does) and be able to give evidence that it is superior to “a parent with a Best Buy camcorder that was purchased for $100.”

Longer term, according to Kulkarni, there may be a chance to think about how to assist clubs in bringing that content to a wider audience, particularly using highlights and concentrating on the best of the best in amateur games, which are of course the forerunners to some of those players one day becoming well-known elite athletes. (For some background, consider how thrilling it is to see video of Michael Jordan playing as a young student.) He predicted that “AI would be able to pluck out the greatest 10-15 plays and stitch them together for highlight videos,” something that might have an audience among sports fans rather than just the parents of the real players.

The market for sports, which has begun to feel ravenous, is fueled by all of this, and it has, if anything, become even larger at a time when many people are spending more time at home and watching video in general. Teisbaek stated that “the sport gets better, for players and viewers, the more film you acquire from the sport.”